Thursday, October 18, 2018

‘Official Cherokees’ disrespecting mixed-ethnicity Americans?

By Steve Hammons

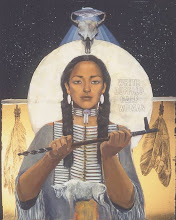

In recent days a robust, if often misguided, national conversation has taken place in our country: Who is a Cherokee?

The questions and answers about this interesting and important subject have been influenced by politics, lack of understanding of U.S. history and Cherokee history, “white guilt” and an odd kind of reverse racism.

Well-meaning journalists and others have dismissed and disrespected millions of Americans who likely have Cherokee ancestors in their family trees.

In the spirit of supporting an abused and oppressed underdog and minority, the Cherokee, good-intentioned people are jumping on the bandwagon to trash anyone who claims Cherokee heritage but is not an official member of one of the three U.S. government-approved Cherokee groups.

Some reactions in the media do not appear to reflect knowledge of American history regarding the highly-significant blending of the Cherokee culture with the early Anglo, Scottish and Scots-Irish arriving in North America.

There was a robust degree of intermarriage between Cherokees and Anglo, Scottish and Scots-Irish in the Appalachian region throughout the 1700s. The children from these marriages then married, and as the generations rolled on into the 1800s and 1900s, this Cherokee cultural heritage and genetic material were spread far and wide, not only in the Appalachian region, but in families throughout the U.S.

TRAUMATIC DIASPORA

For thousands of years, the Cherokee lived in the Appalachian region that today we call Kentucky, Tennessee, West Virginia, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama and Georgia. That is the ancestral homeland, though there reportedly are accounts from other tribes that recall ancient times when the people we now call the Cherokee may have migrated from elsewhere.

The forced removal of the Cherokee from this homeland prior to and during the organized ethnic cleansing known as the Trail of Tears was traumatic, some might even say criminal, as it resulted in thousands of deaths including the elderly, children, babies and adults.

Yet, some Cherokee were able to avoid the removal. Perhaps they hid out deep in their beloved mountains and avoided the soldiers. Perhaps they fled to surrounding regions.

And those of mixed ethnicity, who had adopted Anglo, Scottish or Scots-Irish names from their fathers or grandfathers, and had lighter skin, might have tried to “pass as white” out of necessity.

At the same time, many mixed-ethnicity Cherokee/Anglo/Scottish/Scots-Irish faced the horrific trials of the forced removal and the long, terrible journey to Oklahoma.

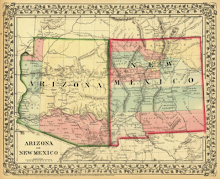

Today, two of the three Cherokee groups recognized by the U.S. government are in Oklahoma, with the group called The Cherokee Nation being the largest by far.

And in the east, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians remains based in the heart of the ancient homeland in the region of the border between eastern Tennessee and western North Carolina.

It could be argued that generations of people with various degrees of Cherokee ancestry who remained in the Appalachian region actually remained closer to the roots of Cherokee culture and history. They stayed close to the deep, dense forests of the mountains and valleys. Close to the trees and lush plant life. Close to the wildlife such as bears, the other animals large and small, and the birds of the forests. Close to the creeks, streams and rivers, and the fish and living things in them.

They stayed close to the deep, deep memories of eras long ago.

HOME SWEET HOME

In recent days, our national discussion has included the nature of the biological genetic material DNA within the body’s cells as well as culture and history. We have talked about psychology and human behavior.

All quite interesting, but have we understood the situation in a comprehensive and accurate way?

As far as ethnic percentages, there is no doubt a long continuum of fractional percentages of Cherokee lineage for many people in the U.S. – from full-blood, to half, quarter, sixteenth, etc. There are people raised with similarly varied proximity to Cherokee geography, history and culture.

Growing up in the region around Oklahoma, Texas and Arkansas would certainly expose people to a good degree of Cherokee culture and history, and that of multiple other tribes that were relocated there.

Likewise, the old Cherokee homeland region that includes Kentucky, Tennessee, West Virginia, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama and Georgia also retains a significant degree of connection with Cherokee and Native American culture and history.

Many, many people who live in this region today, and have for generations, are conscious of their Cherokee heritage. Others might suspect this connection. And some may be totally unknowing about this possible element of their ancestry.

Cherokee culture and history are part of the Blue Ridge National Heritage Area (a partner of the National Park Service) in the Blue Ridge Mountains of western North Carolina. It includes Cherokee heritage events, arts and crafts, music, museums, festivals and more.

How many Americans each year are drawn to visit the many Cherokee-connected experiences in the Appalachian region? And why?

As we try to learn more and understand more about the complex question of “who is a Cherokee?” it might be worthwhile to consider all of the circumstances involved. It’s not black and white – or red and white.

The millions of Americans today who have Cherokee connections in their family trees do not need the official approval of the U.S. government or officials of tribal groups to know who they are. They do not need the recognition of journalists and politicians.

They cannot be disenfranchised from their heritage. Their heritage can be disrespected but cannot be stolen. They know about their deep roots in the Appalachian region and in the Cherokee culture.

(If you liked this article, please see my other recent ones about the Cherokee on the Joint Recon Study Group and Transcendent TV & Media blogs.)