Tuesday, October 16, 2018

Government-approved Cherokees don’t tell whole story?

By Steve Hammons

There are three groups of Cherokees that are officially recognized by the U.S. government. Each maintains their own criteria for membership. Additionally, over the years U.S. government actions and court cases have also influenced membership decisions.

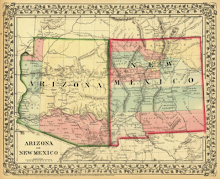

During the so-called “Cherokee diaspora” beginning in the early 1800s prior to the “Trail of Tears" (1838-39), Cherokee individuals, families and communities were spread far and wide, settling in several states.

The three groups currently recognized by the U.S. government are:

- The Cherokee Nation with headquarters in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. This is largest official group and includes more than 220,000 tribal members.

- The United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, also based in Tahlequah, has approximately 10,000 members and is the smallest of the three federally-recognized groups.

- The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians is headquartered in Cherokee, North Carolina, which includes approximately 12,000 members.

Because of the significant degree of intermarriage between Cherokee and mostly Anglo, Scottish and Scots-Irish in the Appalachian region during the 1700s, many Americans today have varying degrees of Cherokee ancestry.

ANCIENT HISTORY

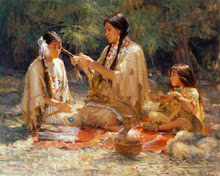

According to the website of the Blue Ridge National Heritage Area website (partner of the National Park Service), “The Cherokee, and what some anthropologists deem to be their pre-Cherokee ancestors, have lived in the mountains of North Carolina since the end of the last ice age, or about 10,000 B.C. The early Cherokee hunted, fished, and farmed, thriving in the rugged mountain landscape.”

“More than a thousand years ago, these people began developing a distinctly Cherokee way of life. They shared decision-making and endeavored to reach democratic consensus on issues. Theirs was a matriarchal society, with land being handed down through the women of the tribe.”

“The Cherokee lived in towns of rectangular log houses and worked extensive, communally-held farms nearby. Corn, beans, and squash—called the ‘three sisters’—were staples in their diet. They also raised potatoes and grew peaches. Each of their towns had a council house for meetings and religious ceremonies,” according to the website.

To put Cherokee culture in context, from about 40,000 B.C. to 15,000 B.C. it is believed that migration to North America from Asia over the Bering Land Bridge occurred during irregular intervals.

During the Paleo-Indian Period, 10,000 B.C. to 8,000 B.C, Native Americans lived a nomadic lifestyle, hunted small and large animals, and ate wild plants.

In the Appalachian region, researchers have documented continuous occupation at Williams Island near Chattanooga, Tennessee, for more than 10,000 years. Hunting camps and artifacts have been found at upper elevations throughout the southern Appalachian mountain range.

According to some reports, ancient Cherokee tales tell of hunting mastodons in Appalachian forests.

COLONISTS WANT LAND

European colonists, who eventually became “Americans” after the American Revolution, arrived and gradually but steadily made their way into Cherokee lands in the Appalachian Mountains.

At first, it was often friendly contact. Daniel Boone, for example, is a common symbol of relatively friendly interactions between colonial explorers and the Cherokee. There were reportedly a significant number of marriages between Cherokee women and Daniel Boone’s contemporaries.

Boone and his associate Col. Richard Henderson purchased the land for the Fort Boonesborough settlement from the Cherokee in 1775. Boonesborough was established in April 1775.

As the decades rolled on, newly-minted Americans started moving west from the colonies on the East Coast into and over the Appalachian Mountain range. Many coveted the Cherokee lands.

By the early 1830s, it was clear to many people that the Cherokees would, sooner or later, be forced off their lands. Many Cherokees saw the writing on the wall and started moving west on their own.

Some Cherokee and their supporters felt they could protect themselves by getting court rulings protecting their right to remain in their homeland. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in their favor. But the court’s ruling was not enforced.

In 1838-39, federal troops and state militia soldiers rounded-up Cherokee, forced them into holding detention camps and finally sent them on harsh forced marches and via other forms of transport to Oklahoma – the “Trail of Tears.” Thousands died.

During this phase of Cherokee history, there were accusations of betrayal and treason against certain Cherokees who were accused of making deals to surrender Cherokee land in the Appalachians. Scores were eventually settled within the Cherokee community, including by murder.

GOVERNMENT-APPROVED CHEROKEES

Today’s Cherokee groups that are recognized by the federal government are related to multiple census lists, known as “rolls.” These rolls were developed and completed by government Indian agents and others over the years for a number of different purposes.

Many Cherokee were undoubtedly not included in these rolls, either inadvertently or intentionally, by the census takers or by Cherokee themselves. For the 1835 Henderson Roll ("Trail of Tears Roll") it’s probable that many Cherokee were living way out in the mountains or away from the census-takers, and who may have wanted nothing to do with these whites doing a head count of the Cherokee.

The rolls ended up including and excluding many Cherokee.

Some of these rolls are related to the eastern Cherokee, some to the Oklahoma Cherokee and some involved both:

- 1835 Henderson Roll (“Trail of Tears Roll”)

- 1848 Mullay Roll

- 1851 Siler Roll

- 1852 Chapman Roll

- 1854 Act of Congress Roll

- 1867 Powell Roll

- 1869 Swetland Roll

- 1884 Hester Roll

- 1898 and 1914 Dawes Roll

- 1910 Guion Miller Rolls

- 1924 Baker Roll

Today, certain of these rolls are key to official membership in the officially-recognized Cherokee groups. For example, the Dawes Roll is crucial to membership in The Cherokee Nation. The Baker Roll is important for Eastern Band membership.

The modern history of the Cherokee people, during and since the 1700s, has been plagued by ill-conceived alliances in war, internal disputes and betrayal, and the fragmentation of the Cherokee people.

This, and other obvious external forces, has resulted in what Gregory D. Smithers, PhD, professor of history at Virginia Commonwealth University, calls the “Cherokee diaspora.” His book "The Cherokee Diaspora: An Indigenous History of Migration, Resettlement, and Identity" includes valuable insights about Cherokee history and U.S. history.

This diaspora, the dispersion of a people from their original homeland, seems to continue today, taking new forms in our contemporary American society.

(If you liked this article, please see my other recent ones about the Cherokee on the Joint Recon Study Group and Transcendent TV & Media blogs.)

(Related article “Storytelling affects human biology, beliefs, behavior” is posted on the CultureReady blog, Defense Language and National Security Education Office, Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, U.S. Department of Defense.)