Friday, October 26, 2018

How many Americans have Cherokee connection in their lineage?

By Steve Hammons

Recent national discussions have brought attention to Americans who may have varying degrees of historical, cultural and genetic connections to the Cherokee. These discussions might turn out to be very helpful in achieving greater understanding of Cherokee history.

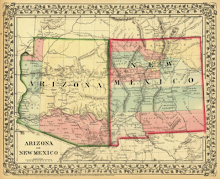

This history is both similar to and different from other Native American tribes. This is true even for other tribes that were indigenous to regions surrounding the old Cherokee homeland in the southern Appalachian mountain range of North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, West Virginia, Virginia, South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama.

Controversies in the media recently have included elements such as:

- Americans with family stories or other indications of Cherokee or Native Americans in family trees

- Degree and scope nationally of Cherokee heritage in the U.S. population

- Animus toward and shaming of Americans who might or do have Cherokee lineage

By learning more about U.S. history and gaining more insight about key factors involved, we could discover that people who might or do have Cherokee in the family tree have no need to feel ashamed or to be affected by shaming.

In fact, this national discussion may lead to increased education and awareness, and prompt more Americans to explore their heritage.

PRESENT AND PAST

What is the scope of Cherokee intermixing with the general U.S. population today?

Gregory D. Smithers, PhD, is an expert on Cherokee history and culture. He is a professor of history at Virginia Commonwealth University and author of the book "The Cherokee Diaspora: An Indigenous History of Migration, Resettlement, and Identity."

In a 2015 article on the website Slate titled “Why Do So Many Americans Think They Have Cherokee Blood?” Smithers wrote, “Recent demographic data reveals the extent to which Americans believe they’re part Cherokee. In 2000, the federal census reported that 729,533 Americans self-identified as Cherokee.”

Smithers noted, “By 2010, that number increased, with the Census Bureau reporting that 819,105 Americans claimed at least one Cherokee ancestor.”

“Census data also indicates that the vast majority of people self-identifying as Cherokee—almost 70 percent of respondents—claim they are mixed-race Cherokees.”

He added, “Today, more Americans claim descent from at least one Cherokee ancestor than any other Native American group.”

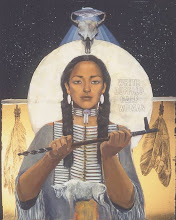

This situation results from a number of factors, according to Smithers. The position that women held in early Cherokee culture and society was one key aspect.

Smithers explains: “When Europeans first encountered the Cherokees in the mid–16th century, Cherokee people had well-established social and cultural traditions. Cherokee people lived in small towns and belonged to one of seven matrilineal clans.”

“Cherokee women enjoyed great political and social power in the Cherokee society. Not only did a child inherit the clan identity of his or her mother, women oversaw the adoption of captives and other outsiders into the responsibilities of clan membership.”

“As European colonialism engulfed Cherokee Country during the 17th and 18th centuries, however, Cherokees began altering their social and cultural traditions to better meet the challenges of their times. One important tradition that adapted to new realities was marriage," according to Smithers.

INTERMARRIAGE ENCOURAGED

During the 1700s, before and after the American Revolution, explorers, hunters and settlers were steadily moving into the Appalachian mountain region. Many of these were Anglo, Scottish and Scots-Irish. This was the recipe for a significant scope of intermarriage with the Cherokee.

Even before that period, Smithers states that intermarriage was accepted or encouraged. In the Slate article, he wrote, “The Cherokee tradition of exogamous marriage, or marrying outside of one’s clan, evolved during the 17th and 18th centuries as Cherokees encountered Europeans on a more frequent basis. Some sought to solidify alliances with Europeans through intermarriage.”

“It is impossible to know the exact number of Cherokees who married Europeans during this period. But we know that Cherokees viewed intermarriage as both a diplomatic tool and as a means of incorporating Europeans into the reciprocal bonds of kinship,” Smithers said.

There were other practical reasons as well as romantic motivations for these marriages, according to Smithers’ research. “Eighteenth-century British traders often sought out Cherokee wives. For the trader, the marriage opened up new markets, with his Cherokee wife providing both companionship and entry access to items such as the deerskins coveted by Europeans.”

“For Cherokees, intermarriage made it possible to secure reliable flows of European goods, such as metal and iron tools, guns, and clothing,” he wrote.

And again, the unique female-oriented culture of the early Cherokee played a role, Smithers claims. “The frequency with which the British reported interracial marriages among the Cherokees testifies to the sexual autonomy and political influence that Cherokee women enjoyed.”

He added, “It also gave rise to a mixed-race Cherokee population that appears to have been far larger than the racially mixed populations of neighboring tribes.”

Over the decades and centuries, this intermixing of Cherokee lineage in the general population continued. This has been widespread, far beyond the Appalachian mountains and the Oklahoma region.

“But the Cherokee people did not remain confined to the lands that the federal government assigned to them in Indian Territory,” Smithers explained in the Slate article.

“During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Cherokees traveled between Indian Territory and North Carolina to visit family and friends, and Cherokee people migrated and resettled throughout North America in search of social and economic opportunities.”

Smithers also noted that, “While many Native American groups traveled throughout the United States during this period in search of employment, the Cherokee people’s advanced levels of education and literacy—a product of the Cherokee Nation’s public education system in Indian Territory and the willingness of diaspora Cherokees to enroll their children in formal educational institutions—meant they traveled on a scale far larger than any other indigenous group.”

(If you liked this article, please see my other recent ones about the Cherokee on the Joint Recon Study Group and Transcendent TV & Media blogs.)

(Related article “Storytelling affects human biology, beliefs, behavior” is posted on the CultureReady blog, Defense Language and National Security Education Office, Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, U.S. Department of Defense.)