Thursday, July 30, 2020

Smallpox-tainted blankets were 1763 bioweapon on northern Appalachian Mountains frontier

By Steve Hammons

Many of us might have heard or read accounts about Native Americans being given blankets tainted with contagious disease during the early Indian wars in an effort to create deadly epidemics among American Indian people.

In situations before, during and after the early colonial Indian wars of the 1700s when this could have occurred, there is often little or no hard evidence.

However, historians have found solid proof of intentional infection of Indian tribes via gifts of smallpox-tainted blankets during spring and summer of 1763 in the northern Appalachian Mountain region. Smallpox is a highly-contagious disease with horrible symptoms, after effects and a high death rate. Even today, it is considered a bioterrorism and bioweapon danger.

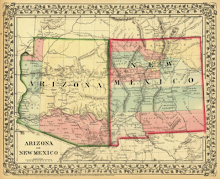

During that 1763 period, British officials, commanders and settlers on the western frontier in the central and northern Appalachian Mountains were facing renewed hostilities with local Native people – Shawnee, Mingo, Delaware and others. And British officials and settlers were eagerly eyeing what they called “the Ohio Country” just west of the Appalachians.

The British military and colonists had defeated the French in the French and Indian War (1754–1763) for control of the region. Now, in the spring and summer of 1763, what had previously been the site of French Fort Duquesne at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers was the British frontier outpost Fort Pitt, built in 1758 (now Pittsburgh).

BRITISH COMMANDERS APPROVE PLAN

After the defeat of the French and their signing of a final treaty with the British, regional Native tribes had also signed agreements with the British. Colonial expansion into Indian lands would be restricted, according to these agreements. Native tribes who had sided with the French to push back British expansion into Indian lands briefly ceased hostilities.

But the Native people saw that after the defeat of the French, even more settlers from the British colonies to the east were invading the Appalachian Mountains. The French were pushed out, now the regional Indians also wanted to halt and reverse the intrusion into their lands by British colonists and officials who also wanted that land.

Those British settlers were also pushing over the Appalachian mountains into the western side of the range – into the lands surrounding the vast river said to be known to regional Indians as the “Ohi yo” or “Ohiyo.”

With more British forts, troops and settlers moving into the region, violence again broke out. This is known as “Pontiac’s War.” There were attacks on settlers and battles with frontier colonial militia and Redcoat troops.

Around Fort Pitt, Shawnee, Mingo, Delaware and others were fighting back against the steady invasion of their lands from British military forces and colonists. By summer 1763 Fort Pitt was under siege by a force of regional Native tribes. The Shawnee and their allies had been attacking British outposts and settlers throughout the region.

The commander of Fort Pitt, Capt. Simeon Ecuyer, along with Col. Henry Bouquet and Sir Jeffery Amherst, then commander-in-chief of the British forces in North America, exchanged correspondence about trying to trigger a smallpox epidemic among their Native adversaries.

Ecuyer had sent word that Fort Pitt was under attack, under siege and in grave danger. Because of the Indian attacks, local colonial settlers had fled to the fort. Additionally, smallpox had broken out at Fort Pitt and was also occurring in the area.

Bouquet, based in Philadelphia, was on his way to Fort Pitt with military reinforcements. In their correspondence, the two men agreed on the plan to infect local tribal communities with smallpox.

At the same time of those communications between Ecuyer and Bouquet, a Fort Pitt fur trader, land speculator and militia captain named William Trent wrote in his diary about including blankets from the fort’s smallpox infirmary in gifts and provisions to Native representatives during negotiations.

In the correspondence and diary entries, there is clear and detailed proof of the intent to spread smallpox among the Indian communities. There are also indications that Gen. Thomas Gage, who replaced Amherst the same year as commander of British forces in North America, also may have known about the smallpox infection tactic.

DEFEND THE OHIYO LANDS

Regional tribes on the western side of the Appalachian Range wanted to force the British and their colonists out of the Ohiyo or Ohio region, and back across to the eastern side of the Appalachians.

During the Indian resistance of Pontiac’s War, it has been estimated that more than 500 British troops were killed. In the Ohio River Valley region, approximately 2,000 settlers may have died during the conflicts.

Native forces destroyed many British forts along the frontier. However, Fort Pitt and two others, Fort Detroit and Fort Niagara, survived.

Due to the escalated warfare, in October 1763, British authorities did issue the Royal Proclamation of 1763. This restricted any expansion of settlement by colonists west of the Appalachian Mountain Range.

But by 1763, many colonists were already increasingly at odds with their British overlords, and this proclamation was widely ignored and not enforced. This issue is regarded as one of the many that triggered the American Revolution. British subjects in North America were not about to stop their quest for the land that lay to the west.

And when the full-scale rebellion broke out, the British called upon regional tribes to side with the King and his Redcoats. Because if these rebellious colonists were not held in check, they would surely further invade Indian lands. Many Native tribes did side with the British during the Revolution for that reason.

When the former British colonists established their new nation -- one they named the United States of America -- the expansion of those former colonists westward would continue to impact Native people in traumatic ways for many generations up to the present day.

Historians apparently are unsure how effective the smallpox-contaminated blankets were in causing an epidemic in the Indian communities involved in the siege of Fort Pitt. Smallpox was an ongoing threat in that era.

However, through intentional or unintentional means, it is undisputed that huge percentages of the Native population of North America died from European diseases. This probably significantly contributed to their military defeats from the 1600s to the 1800s as well as much damage and destruction for many American Indian societies and cultures.

(Related articles “Storytelling affects human biology, beliefs, behavior” and “Reagan’s 1987 UN speech on ‘alien threat’ resonates now” are posted on the CultureReady blog, Defense Language and National Security Education Office, Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, U.S. Department of Defense.)

Saturday, July 18, 2020

Well-known ‘Mothman’ case also about dedicated local journalist, Native history?

By Steve Hammons

The so-called “Mothman” reports around the town of Point Pleasant, West Virginia, in 1966-67 have been widely portrayed in books, TV shows and a popular Hollywood movie.

Real-life researcher and writer John Keel went to Point Pleasant to investigate, where he worked closely with local newspaper reporter and columnist Mary Hyre of The Athens Messenger daily newspaper based in nearby Athens, Ohio. Athens was founded in 1797 and is home to Ohio University, chartered in 1787 and founded in 1804.

Hyre had been following up on reports from local citizens about UFOs seen in the sky (now referred to as “UAP” by the U.S. Navy – “unidentified aerial phenomena”). Then, reports of a large, unusual being also started coming in.

Some Point Pleasant locals reportedly wonder if various odd occurrences in the area are linked to the deeper history there. Long before the UFOs and Mothman allegedly showed up in the area, the October 1774 Battle of Point Pleasant or Battle of Kanawha took place.

Native Shawnee, Mingo and other Indian allies were defeated by colonial militia with British Redcoat involvement in this important battle. The father of Shawnee leader Tecumseh was killed in the battle when Tecumseh was just a boy. Shawnee Chief Cornstalk is said to have asked the Great Spirit for a curse on the land there.

WHERE THE WATERS MINGLE

In the 2002 Hollywood movie version, “The Mothman Prophecies,” based on Keel’s 1975 best-selling book of the same name, Richard Gere plays the Keel-like character. Hyre seems to be represented by actor Laura Linney who plays not a local community newspaper reporter, but a Point Pleasant city public safety peace officer.

The 2019 movie “Dark Waters” starring Mark Ruffalo looks at this same region along the Ohio River. The 2019 best-selling book “The Pioneers” by historian David McCullough also explores the area. In fact, McCullough focuses on Athens and the founding of Ohio University, now home of the respected Scripps College of Communication and E.W. Scripps School of Journalism.

Hyre worked at The Messenger’s news bureau covering Point Pleasant and the surrounding region. She was part of the community and her newspaper column “Where The Waters Mingle” was widely read. Point Pleasant is at the confluence of the Kanawha and Ohio Rivers.

In 1966, Hyre was covering the normal kinds of community events and news topics when reports started coming in of unusual lights in the sky. These reports were from reliable citizens. So, she started following up, conducting interviews with locals about what they saw, and writing articles about the accounts and observations being reported to her.

When Keel arrived in Point Pleasant to investigate, he and Hyre worked together to try to understand and document the unusual reports and unfolding developments in the area. There would be dozens of UFO or UAP reports in the area, maybe hundreds.

These reports of odd phenomena ended up continuing for more than a year into 1967. There were also claims of pets and livestock being mutilated.

And then, on Dec. 15, 1967, the Silver Bridge from Point Pleasant across the Ohio River collapsed. Thirty-one cars plunged into the cold river, 46 died and nine were injured.

Hyre covered it all, as painful as it was for her. Her role as a dedicated journalist and trusted neighbor to the people of the area is a part of the Mothman story that is often overlooked.

Hyre passed on in February 1970 at age 54 after a brief illness. She had worked at The Athens Messenger for 27 years and had served the people of the area as a trusted journalist.

On Sunday, March 30, 1975, The Messenger ran an article with the headline, "Mason 'Mothman Prophecies – Author Keel Dedicates Book to the Late Mary Hyre.” The article recounted how Hyre and Keel joined forces to gather information, attempt to gain understanding and inform their readers.

REAL ESTATE CHANGES HANDS

Could Hyre, Keel and the residents of the region have been dealing with, in some mysterious way, the troubled history of that area – and of our country?

According to some accounts, Shawnee Chief Cornstalk called upon the Great Spirit to curse the land around Point Pleasant because of the treachery and harm caused to the Shawnee and other Indians of the region.

European colonists from Virginia and other colonies were pushing further into Native lands. And some of these colonists and their militias were having increasingly strained relations with their British overlords and Redcoat troops.

Tecumseh, whose father was killed at the 1774 Battle of Point Pleasant, would grow into a leader who would try to unite Native people of the region. He unified many Indian tribes in an alliance to establish a joint-tribal territory.

But, in the 1794 Battle of Fallen Timbers in northwestern Ohio, Tecumseh and his alliance were defeated by frontier militias and forces of the new government formed by the European colonists to the east – now called the United States of America.

The Shawnee were eventually pushed out of all of Ohio. To Kansas, to Oklahoma, to the winds. The Miami or Myaami in southwestern Ohio and Indiana were also forced west to Oklahoma.

The Cherokee, just to the south, intermingled and intermarried with Scottish, Scots-Irish and Anglo pioneers during the 1700s. Many mixed-ethnicity families in the region were created. These cultures merged and a unique population developed. Some Cherokee took up the ways of European colonists and new “Americans.”

Yet, the Cherokee, including many mixed-ethnicity Cherokee, were rounded up, forced into harsh detention camps, and forced west on various versions of the “Trail of Tears” around 1838-39, when thousands died, including babies, children and the elderly.

A so-called “Cherokee diaspora” took place – Cherokee people dispersed far and wide, though many remained close to the homeland in the southern Appalachian mountain area. And many had adopted the Anglo and Scottish names from their fathers and grandfathers, and were as white as they were Cherokee, or more white than Cherokee in many cases. Over the generations, these families intermarried into the larger population of the region and throughout the U.S.

Is this complex and difficult history related in any way to the UFO, UAP and Mothman incidents in Point Pleasant in 1966-67? Were Mary Hyre and John Keel actually encountering something related to a deeper history, an ancient history of that area?

After all, long, long ago, Shawnee, Cherokee and other Native tribes and cultures had been there for thousands of years. They lived in the deep forests and hills. They lived on, traveled on and fished in the many streams and rivers, including the majestic waterway later known as the "Ohi yo" or "Ohiyo."

And generations upon generations were born, lived and passed on in the region “Where The Waters Mingle.”

(Related articles “Storytelling affects human biology, beliefs, behavior” and “Reagan’s 1987 UN speech on ‘alien threat’ resonates now” are posted on the CultureReady blog, Defense Language and National Security Education Office, Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, U.S. Department of Defense.)

Friday, July 3, 2020

‘Hillbilly’ J.D. Vance, columnist Clarence Page find common ground in southwest Ohio roots

By Steve Hammons

Long-time Chicago Tribune columnist Clarence Page and J.D. Vance, author of the book “Hillbilly Elegy” (movie due out soon), have recently acknowledged some overlapping elements of their upbringing.

Both are from Middletown, located between Dayton and Cincinnati in the southwestern corner of Ohio, near the Indiana and Kentucky state lines.

Page, a generation older than Vance, has pointed out that both his father and Vance’s grandfather worked in the same Middletown lumberyard, and that both families struggled financially.

Both Page and Vance have noted that limited economic opportunities contributed to hardships for not only their families, but also for their larger communities. For Page’s family – the Black community. And for Vance’s family – the people in southwest Ohio from southern Appalachia.

In both cases, Page and Vance say that the experiences of their families are similar to those of others from these respective communities.

HILLBILLY HIGHWAY, UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

These two communities have sometimes been perceived and labeled in certain derogatory ways. The two also seem to have several factual historical elements in common, as well as obvious differences.

In the case of southern Appalachian “hillbillies,” often of Scots-Irish backgrounds, they have sometimes been called a dysfunctional group overall, with bad work habits, problematic family relationships, low educational attainment, poor health, drug and alcohol abuse, antisocial behavior, a bad attitude that is rebellious against authority and a chip on their shoulder.

In the case of the Black community, they have sometimes been called a dysfunctional group overall, with bad work habits, problematic family relationships, low educational attainment, poor health, drug and alcohol abuse, antisocial behavior, a bad attitude that is rebellious against authority and a chip on their shoulder.

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to examine the histories of these two groups and see that there are significant similarities that could be related to some of these derogatory perceptions and labels.

Both have a history of being used as cheap labor – very cheap labor – and often trapped in oppressive poverty by external economic, sociological and geographic circumstances for generations while trying to survive and work toward a better life.

Both Page’s and Vance’s families had moved north in years past, north of the Ohio River and into that southwestern corner of Ohio. The general route from the southern Appalachian region into southwest Ohio and points north and northwest is known as the “Hillbilly Highway.”

This is not to be confused with the east-west, officially-named Appalachian Highway, State Route 32, between Cincinnati and Athens, deeper in the Appalachian region. Athens is home of Ohio University (Page’s alma mater) and a key data point in historian David McCullough’s recent best-selling book “The Pioneers.”

The Underground Railroad across the Ohio River and through southern Ohio was another north-south route taken by many people who were also seeking a better life. Today, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center is located in downtown Cincinnati near the Bengals and Reds stadiums on the banks of the Ohio River. After the Civil War, of course, many people headed north for a number of reasons.

SHAWNEE, REVOLUTIONARY VETS, QUAKERS, GERMANS

Some or many of the experiences of the families of Page and Vance in southwestern Ohio are probably related to the deeper historical background of the area, in one way or another.

Long before the Civil War period, Revolutionary War veterans and other settlers moved into the area as the Shawnee and other Native tribes in the region were being pushed out. Cincinnati was named for a Revolutionary War Continental Army officer veterans’ group.

After the Revolutionary War, the land rush into “the Ohio Country” was on. The Shawnee and other regional tribes fought many battles to protect their land and way of life. But, in the end, they were militarily defeated.

Quaker settlers had arrived in southwestern Ohio in the early 1800s and continued migrating to that area and others north of the Ohio River. In their own way, they tried to help the defeated Shawnee and other tribes, sometimes through misguided approaches. Regional Quakers were reportedly very involved in the Underground Railroad and anti-slavery abolitionist movement.

Several waves of German immigrants arrived in the southwestern Ohio area in the mid-1800s. Cincinnati was a major center for German immigrants and is still a center of German-American culture today. Cincinnati is one point of the "German triangle" of German immigrants and settlement, with St. Louis and Milwaukee being the other two points of the triangle.

Some people might associate German-Americans of the region with loyalty and ideological issues during World War I and World War II. However, German-Americans from Ohio fought bravely for the Union in the Civil War. Several all-German-American regiments from Ohio and elsewhere in the North fought in major Civil War battles.

So, it’s probably fair to say that Page and Vance are both products of similar and common experiences, not only of their growing-up years in Middletown, but also of certain larger contexts of American history and the history of southwestern Ohio.

(Related articles "Navy Research Project on Intuition," "Human perception key in hard power, soft power, smart power" and “Storytelling affects human biology, beliefs, behavior” are posted on the CultureReady blog, Defense Language and National Security Education Office, Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, U.S. Department of Defense.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)